Exactly one year ago the Global Summit on Ending Sexual Violence in Conflict brought together governments, donors, multilateral agencies and civil society globally for the first time to discuss action on addressing sexual violence against women and girls in emergency contexts. This UK-hosted summit focussed on transforming political commitments into practical action. It was built on the foundations of the Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict , launched by the UK government in September 2013, and the November 2013 Call to Action on Protecting Girls and Women in Emergencies Communiqué. To date, 140 governments have endorsed the declaration and 32 governments are signatory to the Communiqué.

The global summit, declaration and Communiqué all led to agreements to strengthen funding to respond to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The global summit recommended: “Donors need to make longer-term funding commitments (beyond one year) in order to build necessary systems and long-term engagement with communities; funds should be made accessible for local level organisations and leveraged from other areas.” [i]

Funding pledges totalling over $US41 million were made publically by donors as a result of the Communiqué and over US$15 million as an outcome of the global summit.

Have these global agreements increased funding for action on SGBV?

Funding to address SGBV remains low though has increased between 2012 and 2014

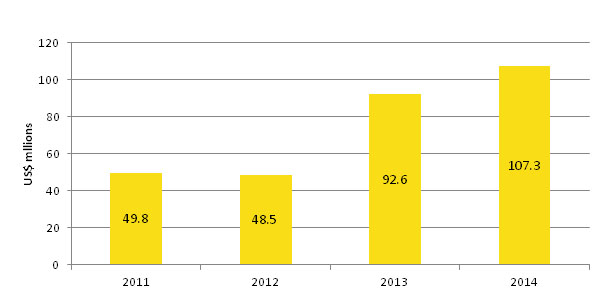

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN OCHA FTS data

Note: Funding analysis captures SGBV-related projects reported to UN OCHA’s FTS. As there is currently no identifier or marker specifically for SGBV in the FTS, a keyword search was undertaken on project titles and descriptions. Thus, the analysis may not capture all SGBV-related funding, particularly where activities are mainstreamed across all other programmes, and/or where funding falls outside of humanitarian spending (ie what is reported to the FTS).

Figure 1 shows that humanitarian assistance for action on SGBV doubled from US$50 million in 2012 to US$107 million in 2014. The increase in funding during this period mirrors the growth of political attention to, and policy commitments related to, SGBV from 2013, culminating in the global summit in 2014.

Funding to SGBV increased from US$93 million in 2013 to US$107 million in 2014, illustrating an increase of US$14 million during the year from the signing of the Communiqué in 2013. This is less than a third of the total pledged by donors following the Communiqué (over US$41 million).

Despite the rise in funding to address SGBV overall, it continues to be low, and only constituted 0.6% of total humanitarian assistance reported to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affair (OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) in 2013, decreasing slightly to 0.5% in 2014.

Levels of funding to address SGBV may, however, be higher than these reported figures. This may be because SGBV activities that are mainstreamed within other programmes are not captured in this analysis. This analysis has largely only captured projects that include an explicit reference to SGBV (or related terms) in the project description as it is not possible to capture mainstreamed spending on SGBV using current reporting mechanisms. Also, additional SGBV activities may be funded through non-humanitarian activities (i.e. development or stabilisation activities) that are not captured in the FTS and are beyond the focus of this analysis.

Furthermore, just under half of SGBV funding (49%) identified in this analysis was not coded using the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) gender marker in 2014 (but captured through Global Humanitarian Assistance coding). Poor reporting on gender using the IASC gender marker is a challenge across humanitarian funding more broadly. In 2014, less than a third (62%) of all humanitarian funding reported to UN OCHA’s FTS was not coded using the gender marker. As a result, it is difficult to track the delivery of policy commitments on gender and SGBV.

South Sudan was the largest recipient of SGBV-related funding in 2014

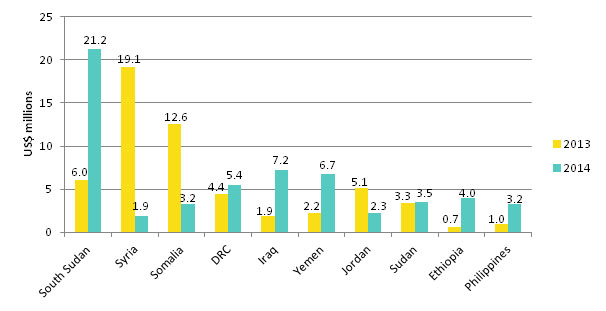

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN OCHA FTS

Based on the available data, South Sudan was the largest recipient of humanitarian assistance for SGBV-related projects, receiving US$21.2 million in 2014, almost three times as much as the next largest recipient Iraq (US$7.2 million). It overtook funding received by the largest recipients in 2013, Syria and Somalia (US$19.1 million and US$12.6 million respectively). Yemen received US$6.7 million and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), often the focus of global SGBV attention, US$5.4 million (an increase of 22% from 2013).

The way forward

To ensure the momentum built from last year’s Call to Action and Global Summit is not lost, it is critical that donors meet the funding pledges made and continue to channel funding towards the goal of addressing SGBV against women, girls, boys and men in emergencies. This would also align with the proposed post-2015 sustainable development goals’ stand-alone goal on gender equality.

Better reporting is also needed so the levels of funding can be properly understood and tracked. Two improvements would facilitate this:

- Better reporting using the IASC marker. As noted in our briefing note on ‘Funding gender in emergencies’, a mandatory commitment from all donors to use this marker when reporting on humanitarian spending to the UNOCHA’s FTS – for UN appeals and more widely – would help to better track overall funding for gender equality and so help to identify SGBV funding within this.

- Adopting a code for reporting on funding that is specifically targeted at addressing SGBV within the existing IASC gender marker and/or within the FTS. This would help to identify specific funding to address SBGV whether for mainstreamed or standalone projects and to track commitments against pledges.

Methodology

Funding analysis captures SGBV-related projects reported to UN OCHA‘s FTS. As there is currently no identifier or marker specifically for SGBV on FTS, a keyword search was undertaken on project titles and descriptions.

The keyword search focused on capturing projects with a description including any of the following: SGBV, gender-based violence, GBV, basees sur le genre, violences basées sur le genre, VBG, basées sur le genre, violences sexuelles, violence sexuelle at basée sur le genre, VAWG, gender based violence, violence against women, , sexual violence, violence-affected children, adolescents and women, sustaining girls’ and boys’ rights to protection from violence, exploitation and abuse in humanitarian settings in Sudan, violence against girls.

[i] UK Government (2014) Summit Report: The Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict.