New aid rules allow for the inclusion of a wider set of peace and security activities

Ensuring transparency and illustrating the development impact of funding decisions will be critical to ensuring that the needs of vulnerable people are met

Last week, at the High-Level Meeting of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), governments agreed to new rules that allow for a wider set of peace and security activities to be counted as official development assistance (ODA). The communiqué from the meeting maintains that all ODA must continue to have a development purpose. As such, the extension largely applies to a set of new non-coercive security-related activities with a longer term sustainable development objective. Examples include the following.

- Support to the civilian oversight of partner country military forces through, for example, training on issues such as human rights and the prevention of sexual violence. (Training for partner military forces was not included in previous OECD DAC guidelines on what can be reportable as ODA.)

- Partner-country-led educational activities that seek to prevent violent extremism through non-violent means. Preventing violent extremism is a new ODA focus area agreed at the High-Level Meeting last week but is not yet an official reporting category with the OECD DAC financial reporting system. (Previous guidelines stated that activities that focus on combating terrorism could not be reported as ODA.)

- Financing to civil policing activities that seek to prevent criminal activities and promote public safety and the provision of non-lethal equipment. (Such activities were not included in previous guidelines and were limited to training for partner country police in particular areas).

Activities included under the old rules have largely been maintained. Examples include the following.

- Additional costs incurred when provider country military forces are required to deliver development or humanitarian services where capability or assets required cannot be timely and effectively met with available civilian assets.

- Technical cooperation provided to law enforcement agencies to assist with the reform of the security sector.

- Training for partner country police in the governance and management of equipment (excludes training relating to counter-insurgency, intelligence or suppression of political activities).

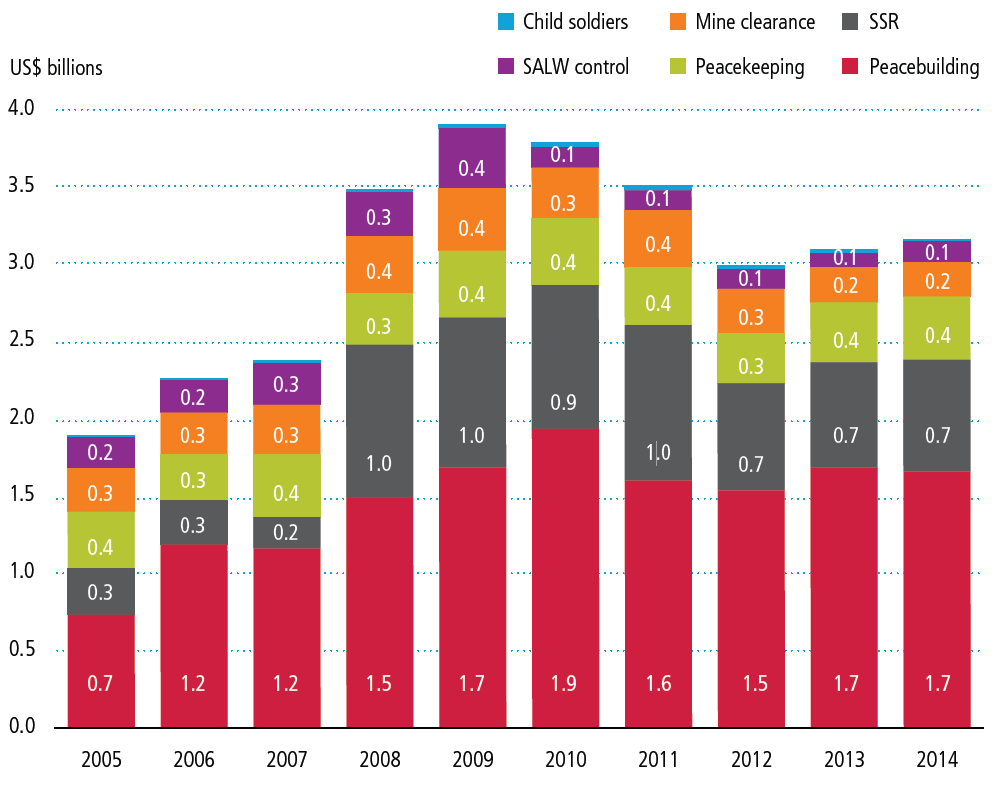

The below chart provides an overview of aid spending on conflict prevention and resolution, peace and security to various sub-sectors during 2014 (as the year that data is most recently available). Funding to the conflict prevention and resolution, peace and security sector has increased by 67% since 2005, reaching a peak of US$3.9 billion in 2009. This peak in funding was largely in response to the crises in Iraq and Afghanistan and a rise in funding to security sector reform (SSR). Funding to SSR increased by US$787 million between 2007 and 2008. During the last decade, ‘peacebuilding activities’ as a sub-category has consistently received the majority of sector funding (52.5% in 2014).

Most ODA on conflict prevention and resolution, peace and security went to peacebuilding activities in 2014

Trends in aid to conflict prevention and resolution, peace and security sub-sectors, 2005–2014

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on OECD DAC’s Creditor Reporting System (CRS) 2014 download.

Notes: Sub-categories stated are abbreviations from the full categories in the CRS.[1] Abbreviations: SALW, small arms and light weapons; SSR, security sector reform.

A diverse range of investments and activities can support the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable people, and more evidence is needed on the linkages between investments and outcomes to inform the allocation of resources. Peace and security is a prerequisite for sustainable development; thus, the inclusion of a wider set of non-coercive activities that seek to reduce the risk of violence, build the capacity of law enforcement agencies to provide public safety, and strengthen civilian oversight over partner military forces is an acceptable modification to aid rules if the beneficial impacts on development and poverty reduction can be demonstated. Such activities could, for example, play a role in meeting the critical security needs of vulnerable people in fragile and conflict-affected countries and in the delivery of global policy commitments that focus on the protection of vulnerable groups in such contexts.

The inclusion of new activities to train partner military forces in the ‘protection of women in conflict and prevention of sexual and gender-based violence’ will create incentives for governments to deliver on associated commitments set out in the UK-led Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict (2013), which has been endorsed by over 120 countries.

However, there is a risk that for some donors, depending on how the wording in the communiqué for the High-Level Meeting is interpreted, these changes to aid rules may result in resources being diverted away from activities with a greater development and poverty-reduction focus in favour of those that align to national security and political priorities. The new focus on ‘preventing violent extremism’ through ODA, which aligns closely with many donor governments’ foreign policy priorities on counter-terrorism, does validate this concern. As a result, the direct impact of ODA on people facing acute poverty and insecurity would be reduced, undermining efforts to meet the ambition set out in the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development to “leave no one behind”. However, this risk does not apply equally to all donors as there are likely to be differences in the way donors apply these rules to their ODA reporting.

To ensure that all ODA continues to be development focussed, it is critical that the following three points are achieved.

- Donors must demonstrate the development-related impact of all ODA spending decisions. ODA is a scarce resource. It therefore must be prioritised for supporting activities that have the greatest impact on the livelihoods and security of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the countries and sub-national regions that need it the most. Donors should systematically demonstrate who has benefitted from assistance, where they have benefited, and the impact such investments have had.

- To achieve this, donors must be transparent and report on all ODA spending on peace and security. This should apply to all government departments that make decisions on the allocation of, and play a role in delivering, ODA-related activities. Timely reporting to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), across all government departments, will help to achieve this in line with donor promises at Busan in 2011.[2] While there are concerns that publishing certain activities to IATI could put staff or populations at risk, a clear policy for deciding which data should be excluded should be developed and by all donor government departments. While some data (such as the names of partners or suppliers in receipt of donor funds) could be excluded for security reasons, this should not prevent other, less sensitive information about the same programme or project from being published. See Development Initiatives’ submission to the UK International Development Committee’s enquiry on the Department for International Development’s allocation of resources’ for more detailed suggestions on how donors’ cross-government transparency on ODA allocation could be improved through IATI.

- Ambiguous wording outlined in the High-Level Meeting communiqué must be clarified. Key areas of the communiqué that need further clarification include the following.

- The document states that ‘intelligence gathering’ cannot be included as ODA; yet, a footnote contradicts this by stating that this does not refer to (and so presumably includes) “preventative or investigatory activities by law enforcement agencies in the context of routine policing to uphold the rule of law, including countering transnational organised crime”.[3] This footnote implies that national intelligence or ‘investigatory’ activities would in fact be reportable as ODA, potentially validating concerns that these new rules may result in the diversion of ODA resources away from addressing the needs of vulnerable people as national security priorities are prioritised. More explanation is required on what types of activities fall within the terms ‘investigatory’ and ‘countering transnational organised crime’, as well as the ways in which they are development related.

- It also states that ‘financing for routine civil policing functions’ and ‘the provision of related non-lethal equipment’ can be reportable as ODA[4] Depending on interpretations, ‘routine civil policing functions’ could apply to a broad range of activities, including coercive law enforcement measures. It will be important to clarify in particular the ways in which such activities contribute to development and how human rights standards will be observed though such assistance. In addition, to ensure that ODA does not result in human rights abuses, it is critical that the term ‘non-lethal equipment’ is defined. The term may be interpreted in different ways, and some ‘non-lethal’ equipment can result in physical harm, such as the use of tear gas and crowd control equipment, undermining the very development focus of ODA.

It is difficult to predict what exact impact these new aid rules will have on aid allocation and the targeting of resources to the most vulnerable people. We will know more when spending decisions are made over the coming months and years once these rules come into force. It is important that donor aid allocation and its impact on poverty reduction and development is monitored closely by parliaments, civil society and concerned governments, with any areas of concern being immediately raised and addressed by the OECD DAC.

Notes

[1] Categories for conflict prevention and resolution, peace and security (purpose code 152) include security sector management and reform; civilian peacebuilding, conflict prevention and resolution; participation in international peacekeeping operations; reintegration; and SALW control.

[2] For more on commitments made at the Busan High Level Forum on Development Effectiveness, see the IATI Annual Report 2015 http://www.aidtransparency.net/annualreport2015/downloads/IATI_Annual_Report_2015.pdf

[3] OECD DAC (February 19 2016), High Level Meeting Communiqué. Footnote 20. http://www.oecd.org/dac/DAC-HLM-Communique-2016.pdf

[4] OECD DAC (February 19 2016), High Level Meeting Communiqué. Paragraph 6. http://www.oecd.org/dac/DAC-HLM-Communique-2016.pdf

Related content

Priorities for the UK’s incoming Secretary of State Alok Sharma

As Alok Sharma takes office as Secretary of State, DI's Amy Dodd sets out key priorities for the UK and its global development agenda.

From review to delivery on the Global Goals – what should the immediate priorities be for the UK government?

On 26 June, the UK government published its Voluntary National Review measuring delivery against the Global Goals - but does it accurately capture progress?

Three priorities for the High-level Political Forum 2019

DI Director of Partnerships & Engagement Carolyn Culey sets out three key priorities for closing the gap between the poorest and the rest at HLPF 2019