Make it count: why and how to track aid for domestic revenue mobilisation

Domestic revenue – the funds that governments raise through tax and other finance streams – will be a key driving force behind implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Yet many of the countries facing the greatest challenge in meeting the SDGs are those where domestic revenues are lowest (see chapter 3 of our 2015 Investments to End Poverty report). Some of the key issues the international community has been discussing are how best to support countries to increase their revenue mobilisation in progressive and sustainable ways and the role of aid for domestic revenue mobilisation (aid for DRM).

Aid for DRM encompasses cooperation in areas such as capacity building for revenue authorities, using new technology in revenue collection or financial management, and introducing and enforcing new tax policies. It typically consists of projects that are small in dollar value, but can have transformative effects. Mozambique, for example, was able to more than double real per capita revenue in six years between 2008 and 2013, in part due to the support of the international community for tax reform projects.

Last year, at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development in Addis Ababa, a group of donors, multilateral organisations and developing countries established the Addis Tax Initiative and committed to double technical cooperation in “the area of domestic mobilisation / taxation” by 2020. This important commitment could create strong incentives to increase aid for DRM and ultimately help increase the revenue available to many countries wanting to implement the vision of the SDGs.

Yet despite the growing importance of this area of cooperation, our understanding of the current situation is patchy, as the systems for reporting ODA spending do not include a mechanism for identifying this component of ODA. In a forthcoming report,[1] we have developed a methodology to address this that identifies relevant ODA projects based on the detailed information on objectives and activities that donors report to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

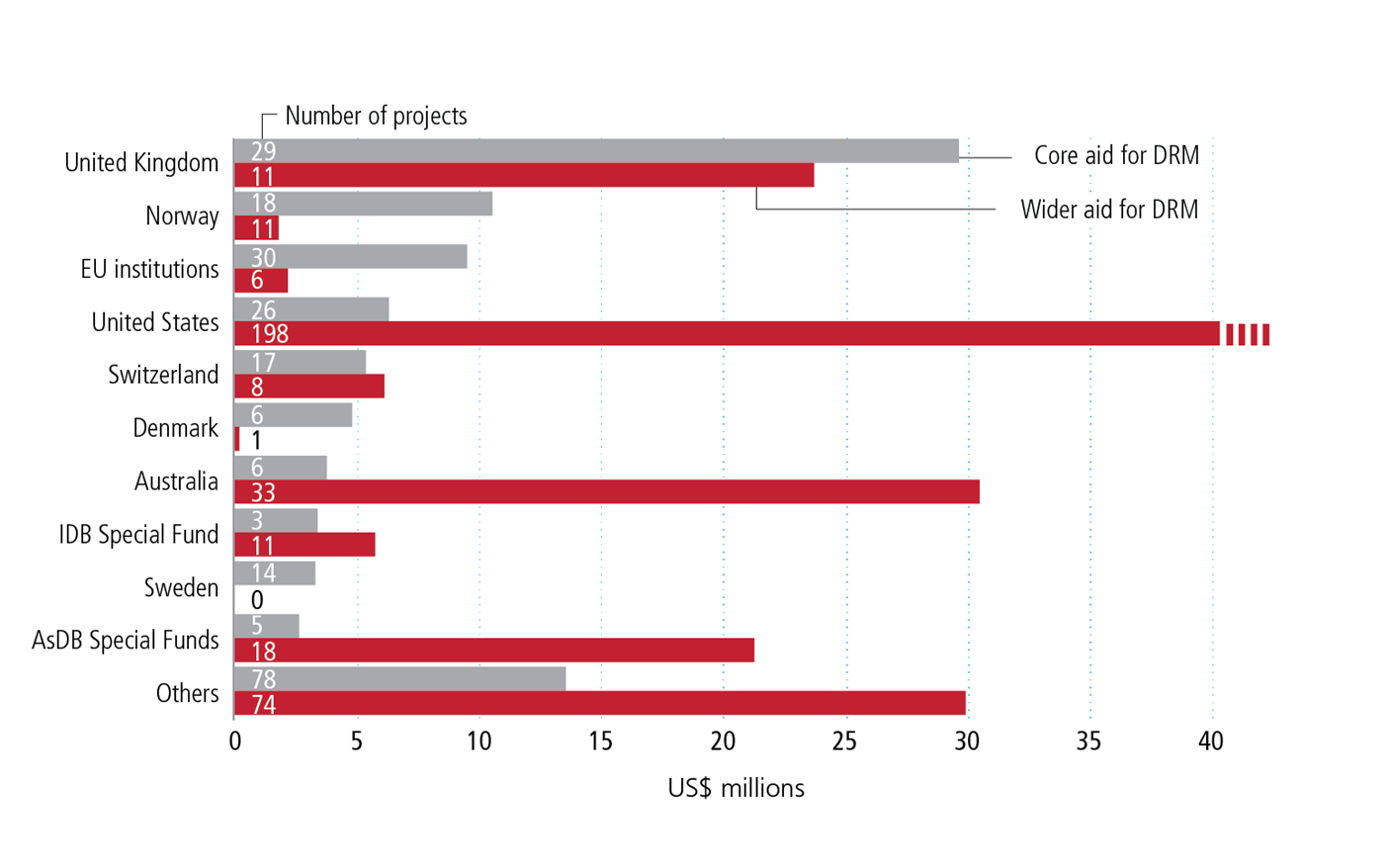

We have identified around 600 aid for DRM projects in 2013, and from within these, almost US$93 million spent on projects that are primarily about increasing revenues (‘core aid for DRM’) and US$600 million spent on projects for which revenue mobilisation is one objective among others (‘wider aid for DRM’).[2]

The UK is the largest provider of core aid for DRM, followed by Norway and the EU (Figure 1). The United States is by far the largest provider of wider aid for DRM, followed by Australia and the Asian Development Bank. The largest recipients of core aid for DRM are Tanzania, Afghanistan and Mozambique.

Figure 1: Largest providers of aid for DRM

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on OECD DAC. Data are for 2013.

Notes: AsDB: Asian Development Bank, IDB: Inter-American Development Bank.

But these are estimates, based on a keyword-search methodology that relies on detailed reporting by donors working in this area and, frankly, a significant amount of patience for trawling through the finer details of the OECD Creditor Reporting System database to identify relevant projects. If we don’t improve reporting of aid for DRM, monitoring cooperation in this area will remain complex and imprecise, hampering accountability and knowledge sharing and limiting the extent to which we can focus on the more important issue of results.

As aid for DRM grows in prominence we need corresponding improvements in clarity about the cooperation happening now, which aspects of the DRM process it is helping countries to improve, and what results are being achieved.

An opportunity to change this is coming very soon, next week in fact, in the form of an OECD Working Party on Development Finance Statistics (WP-Stat) meeting. WP-Stat, the committee that defines how data on official development assistance (ODA) will be reported, is in the process of reviewing how to improve reporting in line with the SDGs. It is looking at how to adjust purpose codes – the sector and sub-sector groups into which ODA projects are classified, and markers – identifiers used to highlight projects that relate to themes such as climate adaption or gender.

This review presents an opportunity to establish a purpose code for domestic revenue mobilisation spending within ODA. A purpose code would provide a simple framework for identifying relevant projects and could allow donors to separate the DRM and tax component of wider aid for DRM projects. Such a purpose code would also allow clear benchmarking and monitoring of the commitments made by the Addis Tax Initiative.

Aid for DRM is an important means by which the international community can help countries increase the revenue they raise. It is an area of ODA that looks set to grow and has the potential to help countries achieve significant gains in the revenues they have available. Taking steps now to provide clarity on the basics of this cooperation – how much is spent, where and how – will help retain momentum for the commitments that have been made. And increasing clarity on what is being spent can help shift the focus to the more important question of what impact aid for DRM is having.

Notes

[1] Aiding domestic revenue mobilisation, to be launched in April 2016

[2] It is not currently possible to isolate the relevant components of these projects, which often cover a wide array of cooperation related to areas such as public finance management or decentralisation.

Related content

Priorities for the UK’s incoming Secretary of State Alok Sharma

As Alok Sharma takes office as Secretary of State, DI's Amy Dodd sets out key priorities for the UK and its global development agenda.

From review to delivery on the Global Goals – what should the immediate priorities be for the UK government?

On 26 June, the UK government published its Voluntary National Review measuring delivery against the Global Goals - but does it accurately capture progress?

Three priorities for the High-level Political Forum 2019

DI Director of Partnerships & Engagement Carolyn Culey sets out three key priorities for closing the gap between the poorest and the rest at HLPF 2019