International Open Data Conference, extractives sector and Joined-up Data Standards

Prior to the International Open Data Conference in Madrid, I was invited by the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) to participate in the extractives data deep-dive. During this event data users and experts discussed how to best visualise an emerging data story, investigated the nitty-gritty detail of complex datasets and shared their latest analyses. Participants from all over the world were able to discuss different experiences and lessons learnt from their latest work. It was in this environment that the comparison between mandatory disclosure data and Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) figures was brought to the group’s attention by Anton Rühling from Open Oil and David Mihalyi from NRGI.

My own understanding of the issue is that the EITI standard data represents a country’s own reporting of extractives activities, such as tax and legal frameworks, production and revenues. Mandatory disclosure of payments to government in France and Great Britain, on the other hand, provides a wealth of reports on companies’ payments over US$100,000 to the government where they operate in this sector. The two reporting systems should complement each other – tracking companies’ activities in a given country and tracking what that country is reporting. As such, these two data sources should allow for double-checking of payments to governments. In EITI’s own words “The EITI and mandatory disclosure are not in an “either/or” relationship. Good management of natural resources needs both these processes and more.”.

Below we re-publish a blog by Paul Dziedzic, originally hosted on the OpenOil webpage, “How do mandatory disclosures relate to EITI figure?” (this analysis spurred out of Publish What You Pay’s “Data Extractors” programme). Here we ponder if the problems that emerge from his data analysis stem from data standards interoperability. As the author writes in his conclusions:

“A comparison, however, proves to be challenging. Important factors to consider range from simple basics such as reporting cycles and comparable currencies up to complex issues of interpretations of what a project is, what can be considered as ‘payments to government’, or the influence of company shares on payment figures.”

It becomes apparent then that the issues encountered are not too far removed from the results of our research.

In our work we advocate for a joining-up of the classifications to conserve the meaning and make contextual translations between data standards and explore how data can be joined-up. For example, the disparities between the definition of a project in the EITI or the currencies reported, as highlighted in the blog, are just two of the problems that stem from not speaking the same language across data standards. It seems that extractives provide a prime example of how necessary joining-up of data, definitions and classifications is.

Fundamentally, the aim of the EITI is to promote national debate and inform policy. However, at the heart of the data problem in the extractives sector is that similar data is being provided by a number of different data publishers in varying formats: between countries and across subsectors. If there is data available now that essentially describes the same thing it should be comparable in one way or another.

Comparative analyses are currently challenging and very time-consuming even for experienced users and this problem is not unique to extractives data. Imagine though if these data standards were linked in a machine-readable format. What if getting the meaning and translations between definitions would take you seconds rather than days? If you could investigate information even with limited technical capacity at your disposal, what advances are waiting to be discovered?

The tools are out there and clearly there is a need to link-up data standards, all we now need is the will from data standards setters themselves to help make this a reality.

How do mandatory disclosures relate to EITI figures?

This blog was originally posted by Paul Dziedzic on Thursday, April 14, 2016 on OpenOil website

This year’s introduction of mandatory disclosures in France and the UK will bring about a considerable amount of reports listing extractive companies’ payments to governments.

The mandatory disclosures promise increased transparency, however, we are only at the beginning of a debate on how to best make use of the new data. One idea has already become apparent: comparing the mandatory disclosure data to EITI figures in order to find irregularities.

In the context of our involvement in Publish What You Pays “Data Extractors” programme, we have simulated how such a comparison could look like and formulated a few first thoughts, as detailed in this document. In this, we try to assess how these different sources referring to the same project relate to each other, in fact, how comparable they are after all. In the following, we would like to highlight a few aspects one has to take into account when comparing the two datasets.

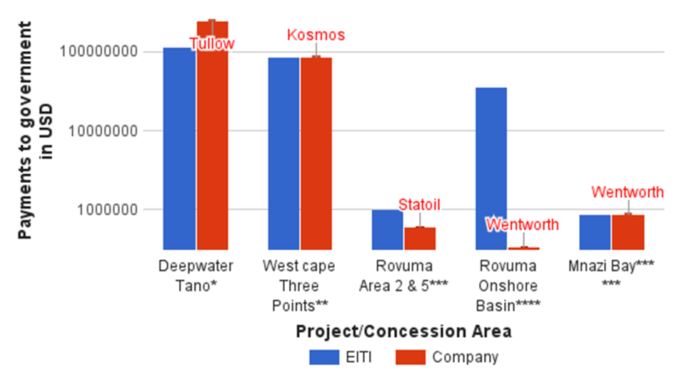

Payments to government 2014 EITI/Company Reports Comparison

Since the most actual EITI reports date from 2014, we needed to make sure the company reports were also covering that same year. This limited our comparison to the four companies in the Oil & Gas sector, that had both published payments to the government reports and that are operating in one of the few countries for which there already is a 2014 EITI report available. In total, we had six cases. The graph above represents the comparison between the EITI data (in blue) and the figures put forward by the companies (in red) on payments to government. In all cases, we found that the two reports had diverging figures. Deviations range from 0.84% (Mnazi Bay) up to almost 200% (Tullow in Rovuma Area 2&5). This begs the question as to why both reports fail to show the same results:

-

Staggered Reporting Cycles

The reporting cycles may diverge. We can see this, for instance, when we want to compare Wentworth operations with the matching EITI reports. These are Mozambique and Ghana. In Mozambique, both reports cover the same timeframe, January 1st, 2014 to december 31st. However, in Tanzania, the EITI report refers to a cycle from June 31, 2013 to June 31, 2014, whereas Wentworth covers January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014.

-

Project / Company Conflation

Some reports relate to projects, other to companies. EITI reports often list payments by companies rather than by projects. However, there are companies that have only one project in the country, which they operate as part of a group. Statoil, for instance, is listed as a company in the EITI reports, and the figure for its payments in the Mozambique is higher than that in Statoil’s report. One reason being that Statoil has only 65% interest in the project. Without the other shareholding companies’ reports, we cannot have a full comparison with the EITI report.

-

What is a ‘payment to government’?

There are differences in what counts as ‘payments to government’. We went through the reports and looked at the items listed as payments. Tullow’s report in the Deepwater Tano project in Ghana for instance includes a range of items that are not included in Ghana’s EITI report, such as VAT, local payroll taxes, withholding taxes or infrastructure improvement. It seems that these items are at the discretion of each EITI member state.

This exercise has shown one methodology to analyse the data around EITI reports and the new incoming data from the EU mandatory disclosures. Although such a comparison proves to be challenging, it might help to prepare a thorough analysis that could lead to a more transparent and standardised reporting, as well as, in the best case scenario, helping to find the missing millions.

This blog was written as a part of the Joined-up Data Standards project, a joint initiative between Development Initiatives and Publish What You Fund.

Related content

Priorities for the UK’s incoming Secretary of State Alok Sharma

As Alok Sharma takes office as Secretary of State, DI's Amy Dodd sets out key priorities for the UK and its global development agenda.

From review to delivery on the Global Goals – what should the immediate priorities be for the UK government?

On 26 June, the UK government published its Voluntary National Review measuring delivery against the Global Goals - but does it accurately capture progress?

Three priorities for the High-level Political Forum 2019

DI Director of Partnerships & Engagement Carolyn Culey sets out three key priorities for closing the gap between the poorest and the rest at HLPF 2019