Humanitarian aid in conflict: More money, more problems?

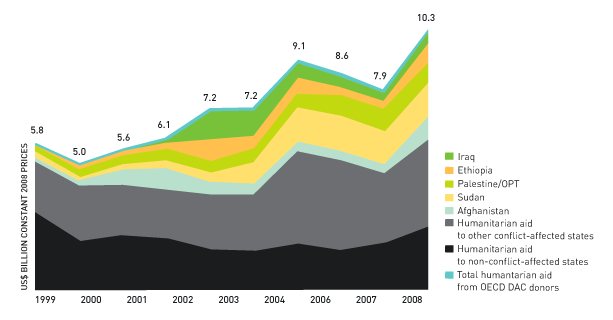

States affected by active conflict or emerging from conflict are major recipients of humanitarian assistance receiving 73.8% (US$7.9 billion) of humanitarian aid from governments and the European Commission in 2008. Of this total, more than US$7.7 billion came from the 23 DAC donors. And despite a reduction in the overall number of active conflicts since the late 1990s, there has been significant growth in the total volume and overall share of humanitarian aid flowing to conflict-affected states.

Growth in Humanitarian Funding to Conflict-Affected States, 1999-2008

Humanitarian aid to the top five conflict-affected recipients by volume dominates the share of total humanitarian aid received by conflict-affected states, accounting for 51% over the ten-year period between 1999 and 2008. Moreover, growth has been concentrated amongst these leading dominant recipients; while humanitarian aid received by conflict-affected states grew roughly three times between 1999 and 2008, humanitarian aid to the top five recipients grew six times. Humanitarian funding to the leading recipients, Sudan and Afghanistan, increased six and eight times respectively. Other notable areas of growth include a ten-fold increase in humanitarian aid to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), from US$52 million in 1999 to US$549 in 2008.

The 2009 Human Security Report describes a paradoxical decline in mortality rates in the world’s current conflicts due to a variety of factors including the life-saving contributions of humanitarian aid. (1) So aid to conflict affected states is successfully saving lives and alleviating suffering, and that aid is increasing so what’s the problem?

Channelling resources into highly insecure environments with acute humanitarian access constraints, where humanitarian actors increasingly rely on sub-contracting to the private sector and are unable to carry out basic accountability checks, offers immense opportunities for major corruption. Earlier this year, the UN Monitoring Group to Somalia published a chilling account of ‘its investigations… on large-scale, egregious and systematic obstruction of humanitarian assistance’, namely corruption within the delivery of WFP food assistance including via three official sub-contractors who receive around 80% of WFP’s US$200 million a year sub-contracted transportation business. The report describes examples reported to the monitoring group of collusion between local WFP staff, transporters, implementing partners and the armed group in control of the area to divert up to 50% of food intended for the population. If these figures are anywhere near correct, (2) that represents a staggering loss of output for a programme that cost US $485 million in 2009. (3)

Recently, an NGO programme manager described to Development Initiatives a typical dilemma facing humanitarian organisations working in Somalia: they were almost certain their local partner, a Somali NGO, was corrupt and could not be certain they were even delivering assistance affected populations, though they could find no evidence of corruption in the organisation’s audit trail. The NGO felt that if they terminated the partnership, they would have no footprint inside Somalia and therefore no capacity to respond if the humanitarian situation rapidly deteriorated. This, she explained, was the dilemma international humanitarian actors faced, should they resign themselves to a ‘see no evil’ attitude to corruption in order to retain some ability to deliver some assistance to Somali’s in desperate need, or should they pull out altogether and leave them to their fate?

This is hardly a new problem and it is certainly not unique to WFP or to Somalia. However, the extent to which humanitarian actors have found themselves compelled to rely on sub-contracting in acutely insecure environments has escalated significantly just as aid to precisely these environments has seen a rapid upturn. The potential for aid corruption to finance nefarious elites and to further destabilise is entirely at odds with the growing donor interest in official funding for ‘stabilisation’, which has seen a twenty fold increase in spending on conflict, peace and security-related activities between 1998 and 2008. (4)

Concerns about aid effectiveness and transparency are resonating in key donor capitals in 2010. Last week, the US Congress put a freeze on US$3.9 billion USAID and State department funding to Afghanistan requested in the 2011 Foreign Operations budget pending further investigation of reports and allegations of diversion, corruption and obstruction of US aid in Afghanistan. (5) Meanwhile, the new coalition government in the UK has affirmed their commitment to transparency in UK aid with a focus on results and outcomes over inputs. (6)

Humanitarian assistance is desperately needed by millions of people affected by conflict, turning off the taps is not an option – humanitarian assistance saves lives in conflict and in fact aid already falls far short of the humanitarian needs of populations in conflict. Aid transparency is crucial but aid in conflict requires an even higher level of accountability throughout the chain of delivery. Donors and delivery agencies operating in highly insecure environments have struggled to keep pace with the challenges to accountability that operating in highly insecure environments with very limited humanitarian access afford combined with growing funding portfolios. Donors and delivery agencies need to urgently develop new modes of operating, new approaches to targeting and accounting for resources and new standards for partnership that revisits the adage to ‘do-no-harm’ if they are to avoid inadvertently fuelling conflict and allowing scarce resources to benefit those for whom it was never intended.

(1) Other factors explained as: ‘First, the long-term forces that have been driving mortality rates down in the developing world in peacetime continue to have an impact in wartime. Second, the relatively small and geographically concentrated armed conflicts that are typical of the current era rarely lead to enough excess deaths to reverse the long-term downward trend in peacetime mortality.’ Human Security Report 2009, published by the Human Security Report Project

(2) It is important to note that WFP has contested the evidence used in the UN Monitoring Group’s report.

(3) Figures as cited in Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia pursuant to Security Council resolution 1853 (2008), 10 March 2010

(4) Spending by OECD DAC donors

(5) See ‘House Panel Slashes USD4B from Obama’s Development Budget’ 2nd July, http://www.devex.com/en/news/house-committee-slashes-usd4b-from-obama-s/68240

(6) See excepts of UK Secretary of State for International Development, Andrew Mitchell’s speech announcing creation of a ‘UK aid watchdog’ on 3rd June 2010, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/media-room/news-stories/2010/mitchell-full-transparency-and-new-independent-watchdog-will-give-uk-taxpayers-value-for-money-in-aid/

Related content

Priorities for the UK’s incoming Secretary of State Alok Sharma

As Alok Sharma takes office as Secretary of State, DI's Amy Dodd sets out key priorities for the UK and its global development agenda.

From review to delivery on the Global Goals – what should the immediate priorities be for the UK government?

On 26 June, the UK government published its Voluntary National Review measuring delivery against the Global Goals - but does it accurately capture progress?

Three priorities for the High-level Political Forum 2019

DI Director of Partnerships & Engagement Carolyn Culey sets out three key priorities for closing the gap between the poorest and the rest at HLPF 2019