Key facts

- Rising levels of forced displacement drive increased emergency financing requirements

- Most displaced people globally are in the Middle East and Africa

- There are more displaced people in middle income than in low or high income countries

- Many countries hosting the most refugees have low domestic revenues

- National poverty surveys in countries hosting the most refugees are largely out of date

- Refugees are not systematically included in national poverty surveys and development frameworks

- Short term emergency responses alone are not sufficient: a wider repertoire of international financing instruments is needed to support refugees, their host communities and national authorities

Displacement and humanitarian financing requirements

1. Rising levels of forced displacement drive increased emergency financing requirements

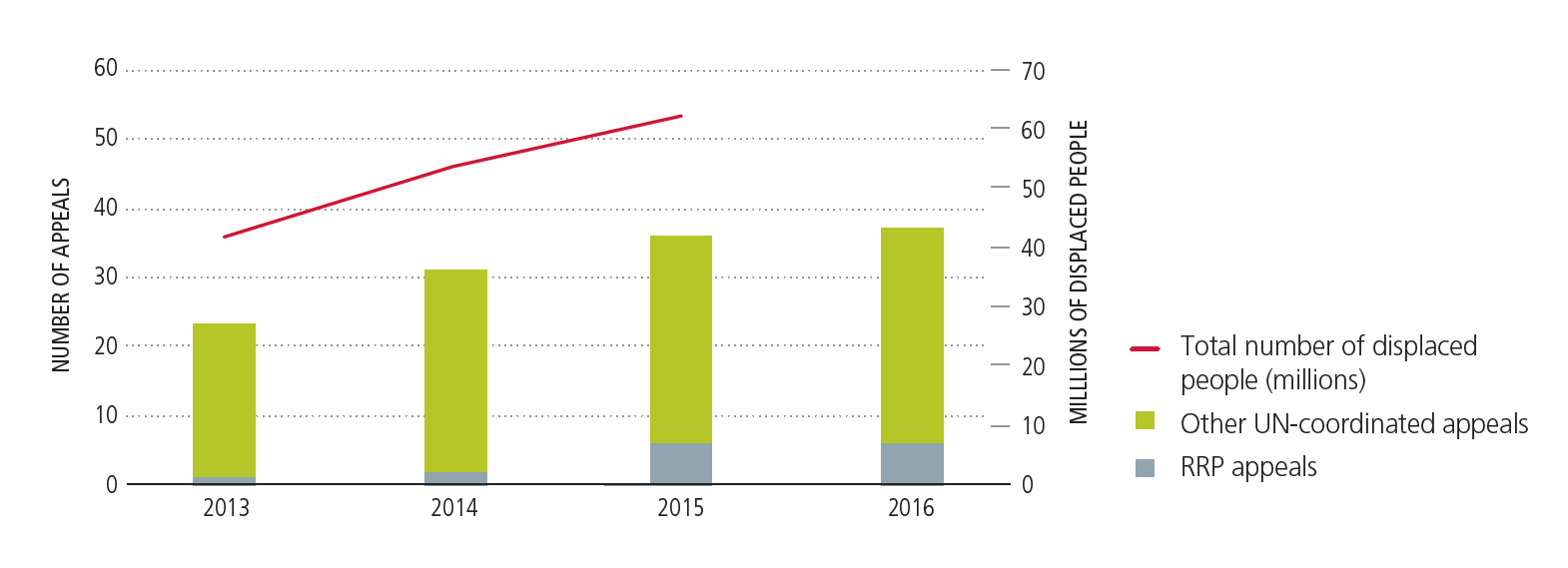

Number of regional refugee response plans (RRPs) against numbers of people forcibly displaced, 2012–2016 [1]

Global forced displacement continues to rise, reaching a record 65.3 million people in 2015 – an increase of 5.8 million people from 2014. The 2015 figure includes 21.3 million refugees, 40.8 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), and 3.2 million asylum seekers.[2]

At the same time, both the number of UN-coordinated appeals and the funding requirements set out within them have risen significantly since 2013, driven largely by major conflicts and complex emergencies that have displaced many millions of people – Syria, South Sudan, Yemen and Iraq among them. In 2013 there were 23 appeals requesting a total of US$13.2 billion, compared to 37 appeals requesting a total of US$20.2 billion so far in 2016. See also Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2016, Chapter 3.

While the needs of many refugees and IDPs are included in country-specific appeals, since 2013 RRPs have set out multi-country approaches to refugee flows stemming from the same conflict. The Syria Regional Refugee and Resilience Response Plan remains by far the largest, requesting US$4.5 billion alone so far in 2016, with five others in 2016 covering displacement from Burundi, Central Africa Republic, Nigeria, South Sudan and Yemen.

But annual appeals and short-term humanitarian funding cycles are clearly ill-suited to addressing the protracted nature of most displacement and the longer-term livelihood needs of refugees and their host communities. The Syria 3RP is multi-year and has a resilience focus in response to the protracted nature of displacement. To support host countries in meeting the immediate and long-term needs of refugees, new longer-term and development financing mechanisms are also beginning to emerge. (see Figure 3 and 7).

The domestic contributions of host countries are also essential. Protecting refugees is primarily the responsibility of states, yet their contributions are hard to measure, particularly as national and local budgets may be difficult to access and assistance cuts across multiple budget lines.

Where people are displaced

2. Most displaced people globally are in the Middle East and Africa

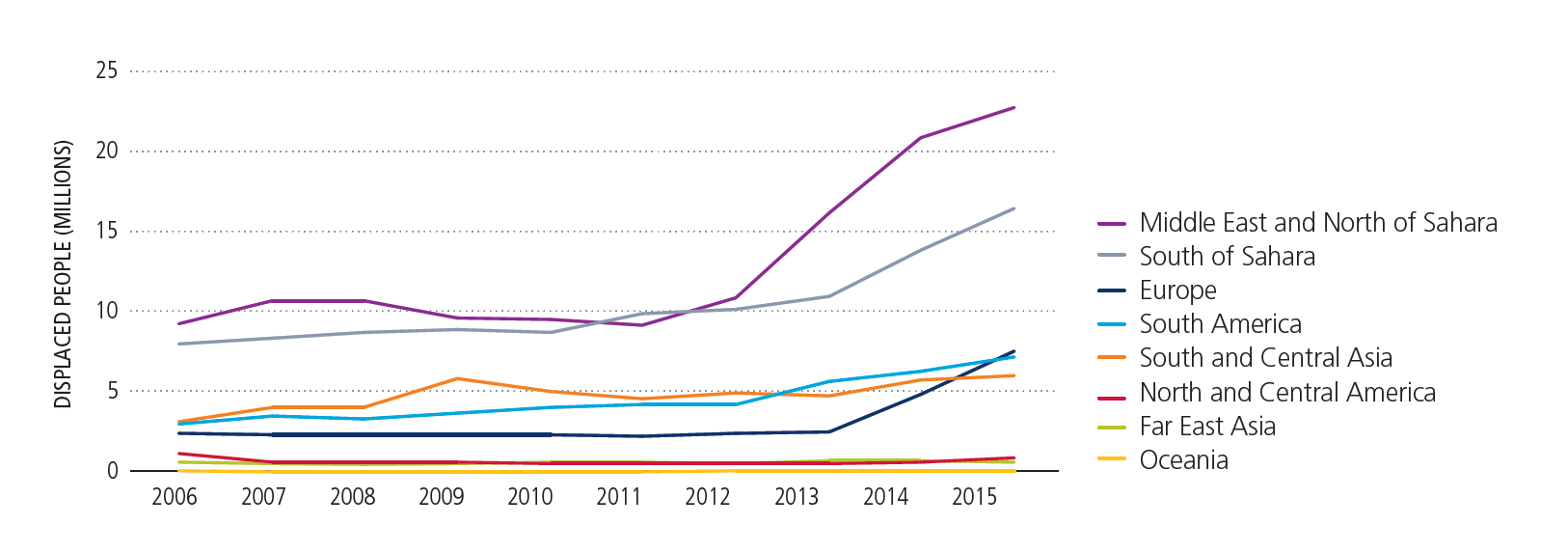

The number of people displaced by region of host country, 2006–2015 [3]

Over one-third of displaced people – refugees, asylum seekers and IDPs – were living in the Middle East and North of Sahara in 2015 (37%), and a further quarter (27%) in the South of Sahara region. So, while the number of refugees and asylum seekers in Europe has risen sharply recently (from 4.9 million people in 2014 to almost 7.6 million in 2015), this represented 12% of the displaced population globally – with most displaced people still in the Middle East and Africa. See Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2016, Chapter 1 for more details.

The wealth of countries hosting the largest numbers of refugees

3. There are more displaced people in middle income than in low or high income countries

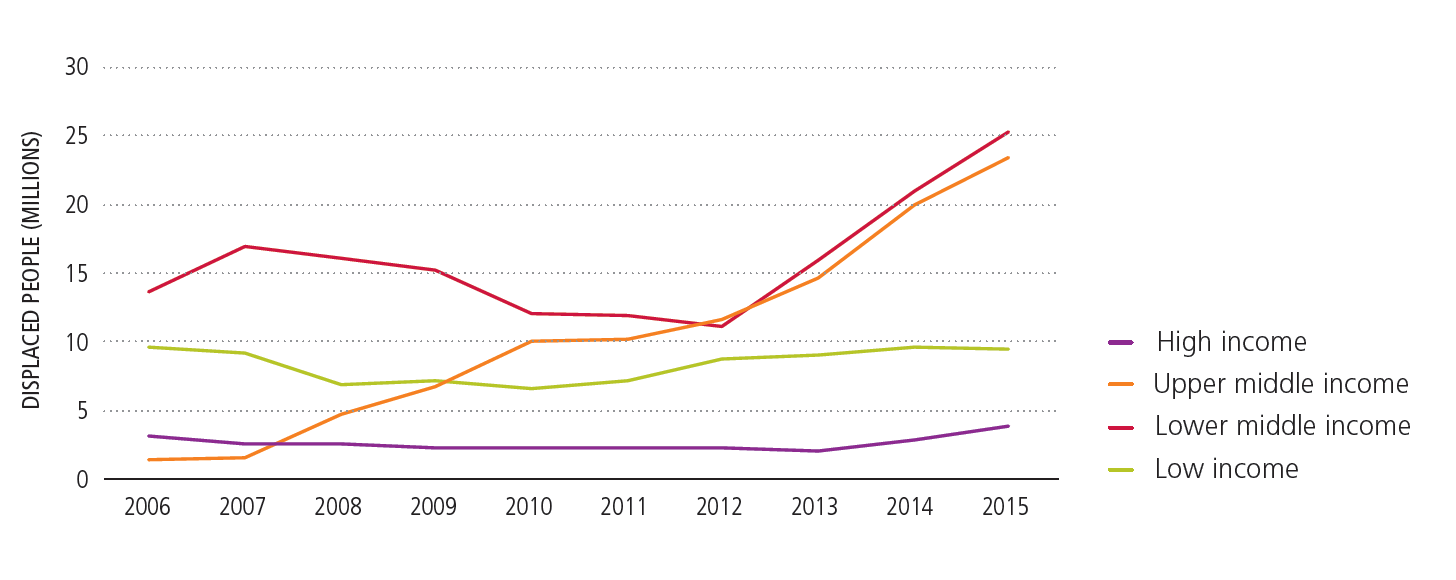

Number of displaced people by income group of host country, 2006−2015 [4]

There continue to be more displaced people in middle income countries (MICs) than in low income countries – with the smallest proportion in high income countries. Lower middle income countries accounted for a large proportion of the total in the MIC group (52%). Although country income levels are wide groupings and a crude indicator of poverty and coping capacity, they can determine the kind of aid a country can access, with the World Bank’s previously applied income criteria making most MICs ineligible for concessional loans. The rising number of displaced people in MICs as a result of the conflict in the Middle East and North of Sahara, particularly in Syria, is impelling a rethink of these financing instruments (See Figure 7).

4. Many countries hosting the most refugees have low domestic revenues

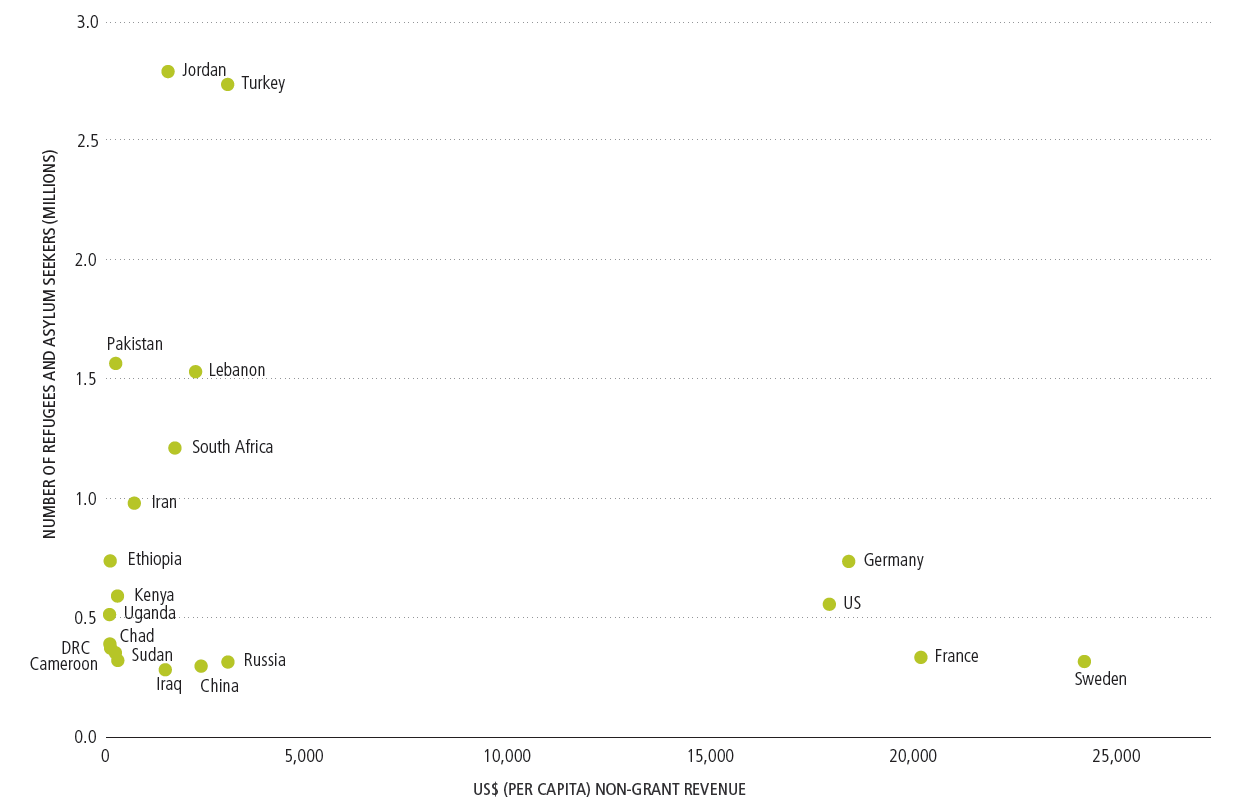

Number of refugees/asylum seekers hosted against non-grant government revenue for the

20 countries hosting the most refugees and asylum seekers [5]

In 2015, Jordan hosted the largest number of refugees and asylum seekers (2.81 million, mostly from Palestine and Syria), followed by Turkey (2.75 million, mostly from Syria) and Pakistan (1.57 million, mostly from Afghanistan).[6] Although the largest numbers of displaced people are in middle income rather than low income countries, many of the countries that host the largest numbers of refugees and asylum seekers generally do not have the highest levels of domestic revenues, and the available national resources to respond are low. For example, Pakistan hosted the third largest numbers of refugees in 2015, but had a non-grant revenue of US$208 per capita. Sweden in contrast hosted a fifth of the number of refugees and asylum seekers as Pakistan that same year, but had revenues 116 times higher (US$24,124 per capita). In Turkey, the figure stood at US$3,400.

Understanding the poverty of refugees

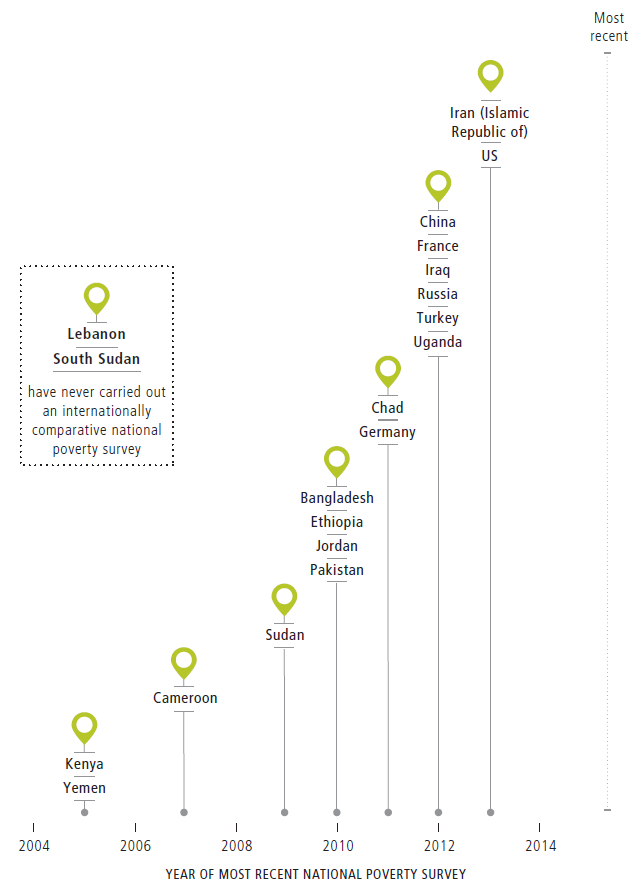

5. National poverty surveys in countries hosting the most refugees are largely out of date

Year of most recent poverty survey in 20 countries hosting the highest numbers of refugees [7]

Understanding the levels of poverty in refugee-hosting countries is important to know the impact on host communities and to be able to appropriately address needs within a development framework rather than in emergency response cycles. However, as per currently available data, only 10 of the 20 countries hosting the largest numbers of refugees have conducted internationally comparable national poverty surveys in the last five years (since 2011), and some – Lebanon and South Sudan – have never had internationally comparable surveys. For most countries, the poverty and crisis context has changed dramatically since the latest national poverty survey was undertaken, meaning that there is a lack of up-to-date information on people’s needs, undermining the potential to plan appropriate support and target available resources effectively. And while poverty data on host communities is limited, data on poverty among refugee populations in these countries is even more challenging (see Figure 6).

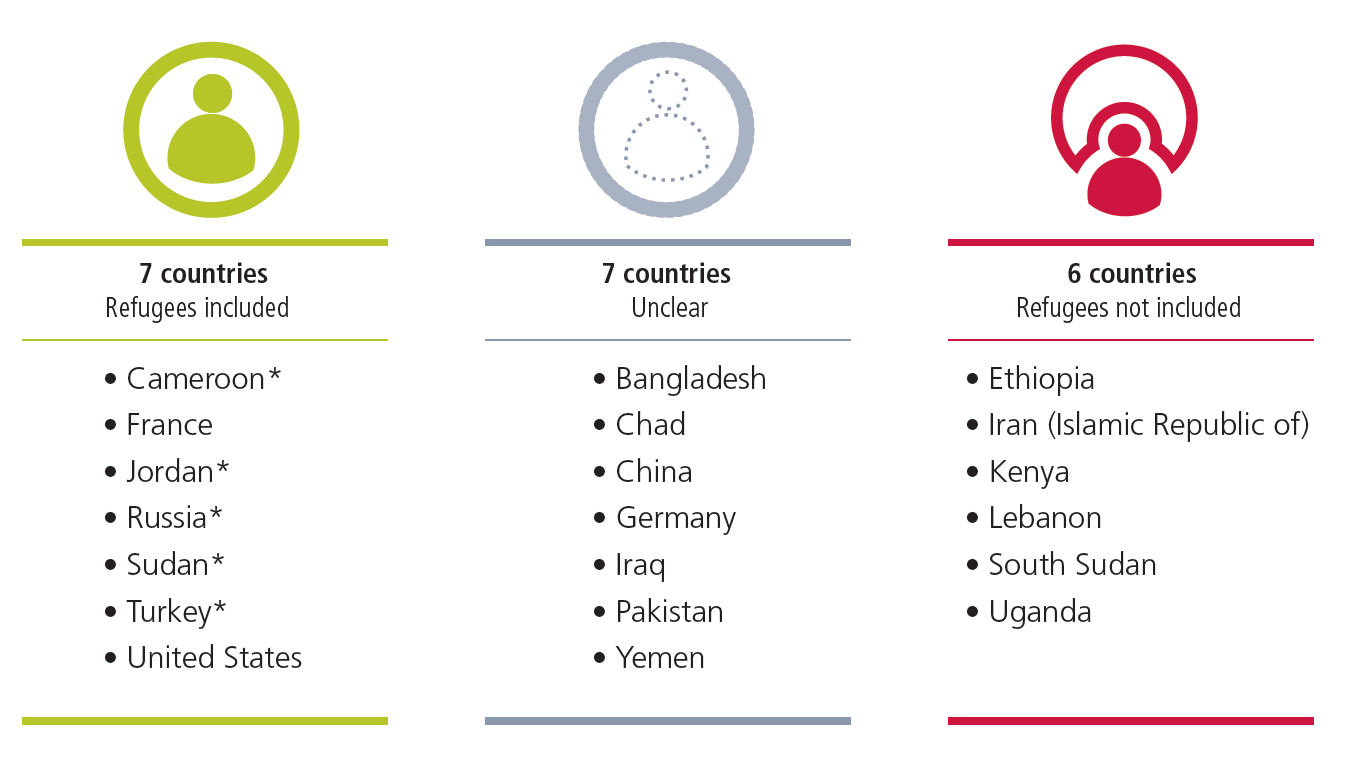

6. Refugees are not systematically included in national poverty surveys and development frameworks

Inclusion of refugees in the most recent internationally comparable poverty surveys in 20 countries hosting the highest numbers of refugees, 2015 [8]

*Countries that did not count those refugees in camps.

Most refugee situations are protracted and it is estimated that on average, refugees are displaced for 17 years.[9] Yet, little is known about the poverty of refugees in their host communities as they are not systematically included in national poverty surveys. So the longer term livelihood needs of refugees are not addressed through national development planning. Instead, these are left to be counted in humanitarian terms and therefore funded through shorter-term emergency assistance. Better data on the poverty of refugees is critical to ensuring that they are not ‘left behind’ in action to meet the Sustainable Development Goals.

Of the 20 countries hosting the most refugees in 2015, only 7 included refugees in their most recent internationally comparable national poverty survey. Of these, five countries only included refugees living in permanent residences outside camps, and hence the surveys do not provide a complete picture of the longer-term livelihood needs of all refugees. What counts as a ‘permanent residence’ outside of camps is often not stated in methodological documents, making it difficult to compare between countries, and risking excluding refugees residing outside camps but not on a ‘permanent’ basis. For poverty surveys undertaken in seven of the countries, whether or not refugees had been included was not explicitly stated in methodologies. There is a need for a clearer and more systematic approach to including refugees in poverty surveys.

In the absence of such national survey data, other studies are beginning to give a picture of refugees’ poverty, to understand their long-term needs and the economic opportunities and development support required. The first poverty and welfare assessment by the World Bank and UN High Commissioner for Refugees of a refugee population took place in 2014–2015 in Jordan and Lebanon, using an approach that can be adapted for other countries. See the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2016, Chapter 1.

Financing mechanisms

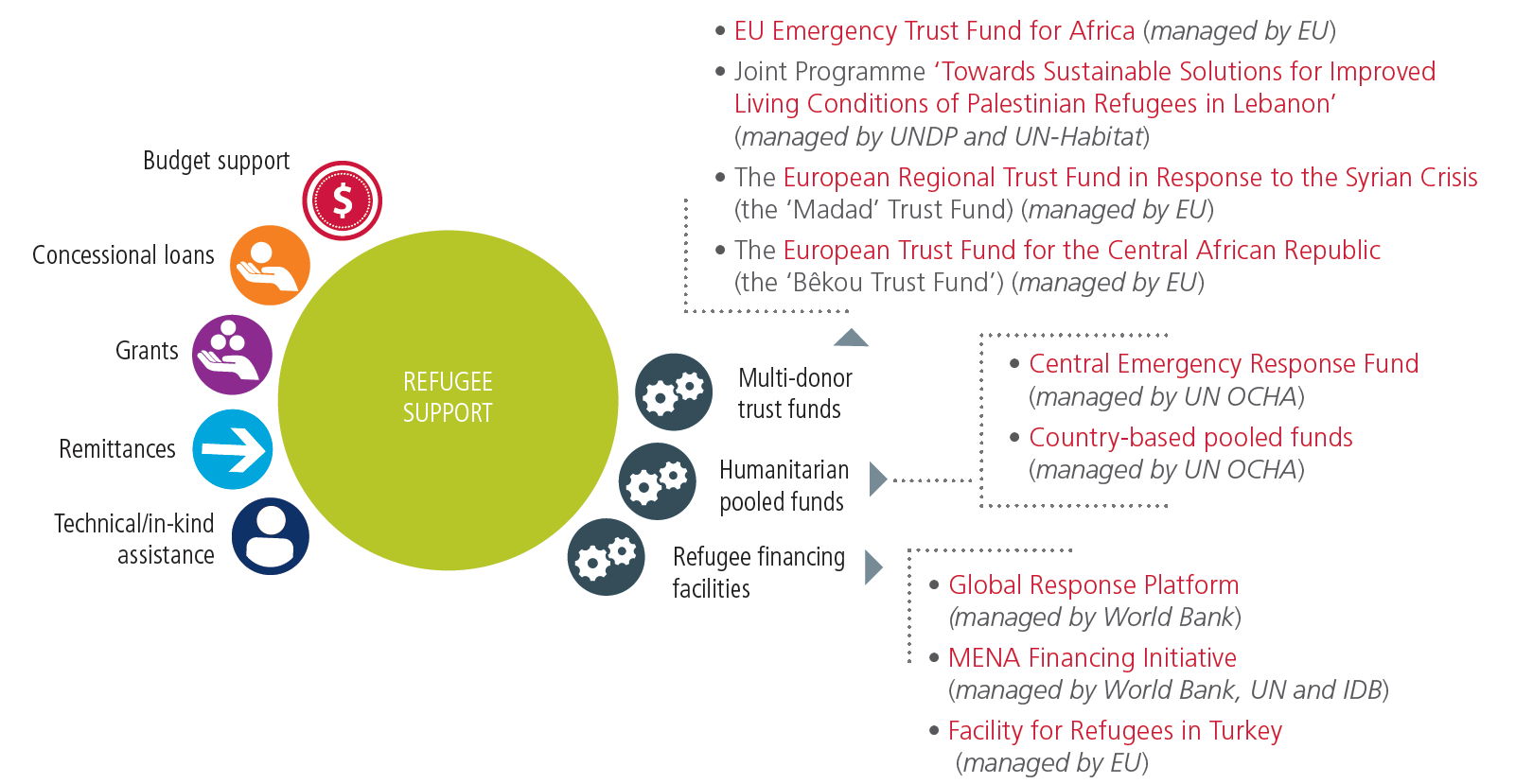

7. Short term emergency responses alone are not sufficient: a wider repertoire of international financing instruments is needed to support refugees, their host communities and national authorities

Modalities and instruments of international financing support to refugees [10]

While refugee responses in places needing international support largely rely on funding from humanitarian grants, this is beginning to change in recognition that emergency cycles are not adequate or sustainable. Greater global responsibility sharing in response to rising levels of displacement[11] includes deploying a more tailored and diverse set of financing instruments to support host countries to meet the immediate and long-term needs of

refugees. An understanding of the existing and emerging mechanisms and resources available in any given context needs to underpin an effective response.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are playing an emerging role in establishing new funding mechanisms to support host countries. At the World Humanitarian Summit, a group of MDBs came together to set out a range of commitments and practical measures to respond to forced displacement.[12] The World Bank’s recently announced global crisis response platform intends to provide resources for risk mitigation and crisis response to low and middle income countries, including access to long-term, low-interest loans,[13] with a particular focus on large refugee-hosting countries.

Within the new MENA (Middle East and North Africa) Financing Initiative, launched jointly by the World Bank Group, the UN and the Islamic Development Bank Group, eight governments and the European Commission pledged a package of over US$1 billion of concessional finance to support countries hosting Syria refugees.[14] It includes guarantees for the issuance of a special type of sukuk (Islamic bond) administered by the Islamic Development Bank Group.

While seeking to support host governments, financing mechanisms also need to build on the capacities of communities, and enable opportunities for refugees. A number of recent studies have evidenced the actual and potential economic contribution of refugees in their host countries, rather than the costs related to hosting them.[15]

Photo credit: EC/ECHO